Hey, I’ve moved! If you enjoy this post you can find more of my writing at Foreign Exchanges, a Substack newsletter covering a variety of topics in history and foreign affairs. Check it out today and become a subscriber!

President’s Day here in the US brings with it a number of anecdotes about the bygone days when the United States was not yet an imperial power and only had intermittent and sometimes eccentric interactions with the rest of the world. You’re more likely today to read about Thomas Jefferson’s war with the Barbary States or about the time Abraham Lincoln turned down the King of Siam’s offer of war elephants (!) than you are on any other day of the year. This seems perfectly reasonable to me, which is why I’m getting in on the action. Today, let’s talk about the 1904 Perdicaris Affair, a relatively minor but interesting little dust-up involving a (former) US citizen named Ion Perdicaris, then-US President Theodore Roosevelt, and a Moroccan outlaw and would-be governor named Mulay Ahmad al-Raysuni, or “Raisuli” as he was more famously known in the American media at the time.

Ion Perdicaris was born in 1840, the son of a Greek immigrant named Gregory, who married into a South Carolina plantation family, served as US consul to Greece, and later moved to New Jersey and helped found the Trenton Gas Light Company. Gregory was a pretty wealthy guy, and Ion accepted the arduous task of helping his dad spend all his money. When the Civil War rolled around, however, the rebel Confederate government figured it could just confiscate any southern land owned by rich Yankee types like the Perdicarises. Ion, who clearly was no dummy at least when it came to keeping his money, headed to Greece to renounce his US citizenship and become Greek, because the CSA wasn’t confiscating land owned by rich European types. Now a citizen of the world, if you will, in the 1870s he moved to Tangier and married an English lady who already had four children by her previous marriage. They were apparently the stars of the Tangier expat scene.

Morocco was, as it still is and as it has been since the 1600s, ruled by the Alaouite Dynasty. The royals are sharifs, which means they can (at least on paper) trace their ancestry back to Muhammad, via his grandson Hasan. They’re the rare dynasty that was able to survive European colonization (which in the case of Morocco meant mostly French and a little Spanish) in the early-mid 20th century (being sharifs may have helped in this regard). In 1904 the head of the dynasty was the young (mid-20s) Sultan Abdelaziz, and he was trying to deal with an empty treasury and the perception, probably justified (but also maybe exaggerated by his enemies), that he was a weak ruler who was a pawn of European powers. One symptom of this perceived weakness was the rise of uncontrollable local bandits like Raysuni.

Mulay Ahmad al-Raysuni was 33 in 1904 and already well into a career as a local bandit and sometimes-pirate, operating usually out of the Jibala region just south of Tangier. One of his favorite pastimes seems to have been kidnapping high-ranking Moroccan officials, along with the occasional European, and then ransoming them. By all accounts he treated his high-status captives well, and befriended many of them, though when it came to people who were too lowly to fetch a ransom he liked to entertain himself with little games like putting out their eyes with red-hot coins. That one always goes over big at parties. Raysuni inspired considerable loyalty among his men, who saw themselves as the noble resistance to the corrupt Abdelaziz, and at any rate Abdelaziz was too weak and/or beset with problems to do anything about him. What Raysuni really wanted was to be pasha of Tangier and governor of Jibala, but he wasn’t able to get enough leverage with his kidnapping business and general brigandage to force Abdelaziz to give him control of those provinces. Ion Perdicaris proved to be his golden ticket.

On May 18, 1904, Raysuni kidnapped Perdicaris and one of his stepsons from their home in Tangier. In return for the safe return of his hostages, he demanded $70,000 and the gigs I mentioned above. These were some hefty demands, and it’s likely that Abdelaziz would’ve told him to take a hike had it not been for the final player in our story, Roosevelt. The president and his Secretary of State, John Hay, were outraged by the kidnapping, or at least knew that it was good politics to act like they were outraged about it, particularly given that it was election season. Roosevelt, as the incumbent (albeit a back door incumbent, having risen to the office due to William McKinley’s assassination in 1901), was probably a mortal lock to be nominated by the Republicans, but the embarrassment of this Perdicaris kidnapping stung, and he and Hay figured that a tough response, or rather the appearance of a tough response, was necessary to shore up his support.

Roosevelt ordered several warships and companies of Marines to Moroccan waters without really any idea what they were going to do once they got there other than look menacing. To an outsider it would have appeared that this show of force was intended for Raysuni, and that the Marines would eventually be ordered to go after the brigand if he refused to return Perdicaris. In reality, the Marines were there to threaten Abdelaziz, who was told in no uncertain terms by Roosevelt, as well as the French and British governments, that he was to meet Raysuni’s demands in order to secure the hostages’ freedom. So much for not negotiating with terrorists. The Marines were presumably also there to make sure that Abdelaziz didn’t blame his capitulation on Roosevelt, lest it be revealed that the president’s tough public face was all for show.

Now, if you’ve been paying attention, you’re wondering, “Why are Roosevelt and Hay involved in this case at all? Didn’t Perdicaris renounce his US citizenship way back in 1862?” If you were wondering that, then pat yourself on the back, because you’re more on the ball here than the US government was. It was only after he’d sent warships to Morocco and demanded that Abdelaziz pay Raysuni off that Roosevelt found out that, actually, Perdicaris had never really been his problem in the first place. He rationalized the whole thing by arguing that Raysuni (or Raisuli) also thought that Perdicaris was a US citizen, which meant that he thought he was going to get away with kidnapping an American, so US honor was still at stake. Yeah, it probably sounded silly back then, too. Making it even sillier, Roosevelt advanced this argument even though he was trying to arrange it so that Raysuni would actually get away with kidnapping an American, and here we can note that the incoherence of US foreign policy is not actually a new thing.

Anyway, Roosevelt and Hay carefully withheld what they knew about Perdicaris’ citizenship from the public, the better to keep up appearances. Meanwhile, as they were demanding that Abdelaziz concede everything to Raysuni, the two men kept talking tough. At the 1904 Republican convention, for example, Hay declared to thunderous applause that “the government wants Perdicaris alive, or Raisuli dead!” I guess “the government will give Raisuli whatever he wants if he lets those people go!” wouldn’t have made for a very good applause line.

Abdelaziz rightly figured that it was better to pay Raysuni off (and keep mum about Roosevelt having demanded it) than to have a bunch of Marines marching down the streets of Fez, so he agreed to Raysuni’s demands and Perdicaris and his stepson were released on June 21. Perdicaris, like other Raysuni prisoners, seems to have befriended his kidnapper during his month in captivity and proclaimed his utmost respect for Raysuni as a “patriot forced into acts of brigandage,” in Perdicaris’ words. This was in stark contrast to several panicky American newspaper reports (many of these are awesome) at the time, which speculated that Raysuni, or Raisuli, or Raissouli, or Fraissouli (???) was likely to kill his captives before any help could arrive. No, I don’t know why his name got mangled in the US media, though he’s certainly not the only foreign personage in history to be so honored.

Perdicaris died in London in 1925, and it wasn’t until 1933 that it became known that he wasn’t an American citizen–Roosevelt and Hay had done a pretty good job of suppressing that part of the story. Raysuni’s victory, meanwhile, was short-lived. Shockingly, the ex-brigand turned out to be a bit of a cruel and corrupt governor, so Abdelaziz removed him from office in 1906. He was appointed Pasha of Tangier again after Abdelaziz was overthrown in 1908, but was removed at the behest of the Spanish government less than a year later. After flirting with the Germans during World War I, he wound up fighting for Spain (suffice to say that allegiances were fluid in this particular time and place) during the 1920-1926 Rif War, when he was captured (1925) by another bandit fighting against the Spanish and died in captivity. Teddy Roosevelt, meanwhile, easily won reelection, and while it’s unlikely that “Perdicaris alive or Raisuli dead!” had much to do with the outcome, it probably didn’t hurt.

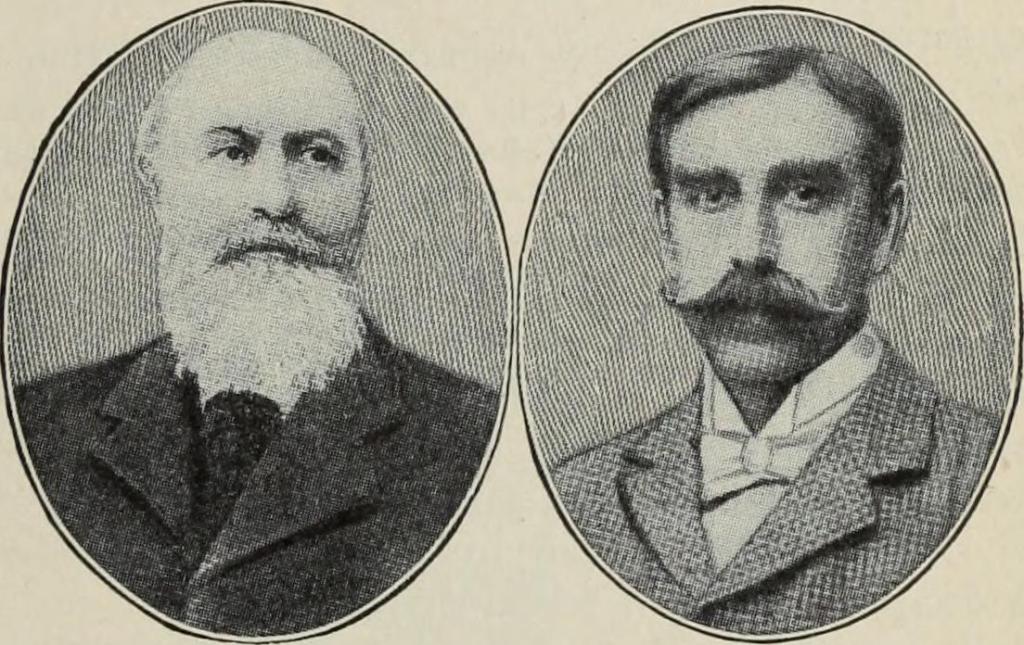

People who are big fans of movie director John Milius might recognize this story as the (loose) basis for Milius’ 1975 film The Wind and the Lion, starring Candice Bergen as Eden Pedecaris, Brian Keith as Roosevelt, and, um, Sean Connery as the Arab brigand “Raisuli.” It’s actually a pretty entertaining movie, though I can’t stress enough that it’s loosely based on the Perdicaris Incident. For one thing, at the risk of repeating myself, Sean Connery is playing an Arab bandit, and a very strapping one, unlike the, uh, larger boned fellow you can see in that photograph of Raysuni above. For another, you may have noticed that “Ion Perdicaris” somehow became “Eden Pedecaris” and is being played by Candice Bergen, who’s a good actress but was definitely not a 64 year old Greek man. Milius figured that the story would be better if the captive were a romantic match for Raisuli rather than some older rich gentleman. I know, why not both, but let’s say it was a much different time in Hollywood and leave it at that.

In the film, the Marines actually do go marching down the streets of Tangier, where they seize the Pasha (who, it’s implied, is the real power in the country) in order to force him to pay the ransom for Pedecaris and her children (two young kids in the film as opposed to the one adult man in real life). The movie ends with Pedecaris and the Marines fighting alongside Raisuli’s men to free Raisuli after he’s been betrayed and captured by the Moroccans and their German allies. Pretty much none of that stuff actually happened. It’s an entertaining film, but lousy history.

For a more fleshed-out version of this story, there are accounts floating around the internet, but Barbara Tuchman’s 1959 piece in American Heritage is probably your best bet. The early-20th Century travel writer Rosita Forbes wrote a biography of Raysuni, called The Sultan of the Mountains: The life story of Raisuli, but good luck finding it anywhere.